It is believed that in traditional societies, architecture was more than the science of construction and the architects besides the knowledge of the built space had to be equipped with thorough knowledge of the human bodies, spirituality and life style. Therefore studying the prescribed rules and patterns of traditional built space is believed to be useful in providing essential information to improve the current architecture in terms of health and wealth of the inhabitants. However since in traditional societies the belief system, rituals and geomancy have had a significant role in prescribing the patterns, it is still highly important to study, experiment and validate them before use. In this article the aim is to introduce and understand what we call traditional sciences of architecture so that in further articles the rules and patterns can be studied in much more detailed approach.

Ancient sciences of architecture are basically a combination of rules and rituals being applied by the master builders and the local craftsmen which has been established and gathered through generations. Although these rules were applied in almost every traditional culture which is also evident in their ritual behaviour and folklore literature, there are few written architectural guidelines remaining today.

Ancient sciences of architecture are basically a combination of rules and rituals being applied by the master builders and the local craftsmen which has been established and gathered through generations. Although these rules were applied in almost every traditional culture which is also evident in their ritual behaviour and folklore literature, there are few written architectural guidelines remaining today.

These established traditional rules and patterns basically have been prescribed considering a number of forces, often described with a French term, “genre de vie;” from which two forces of nature and culture are of great importance. While nature has imposed certain universal structural patterns to the creation of traditional dwellings, known as “low architecture,” culture refers to the unique patterns influenced by the belief system of every nation, known as “high architecture.”

These established traditional rules and patterns basically have been prescribed considering a number of forces, often described with a French term, “genre de vie;” from which two forces of nature and culture are of great importance…

“High architecture” in this case, concerns the spiritual and cosmic rules to define proportion, geometry and ritual acts as representations of the culture in domestic art. Association of earth to vault of the sky, vertical axis and the symbolic forms of space are the manifestations of this high aspect. The “low architecture” on the other hand deals with the climatic issues, the use of materials, technologies and construction methods. While the cosmic aspect is achieved by the prolonged spiritual and esoteric studies, the low scheme depends on the sum experiences of generations dealing with environmental criteria.

Considering the high aspect, traditional architecture is basically in alignment with the traditional rule system or geomancy which used to decide the directions and locations of the buildings and the construction methods accompanied by the ritual acts performed under the preserve of the priesthood which used to give guidance to the craftsmen and builders. In fact performing these acts and principles was an embodiment of cultural values and the representative of symbolic concepts towards the universe. In this way even a simple dwelling was served as a reflection of both material and spiritual realms of its inhabitants.

Concerning the low aspect, the common characteristics of dwelling architecture are the presence of environmental context in which the buildings have been raised, the use of local materials which creates a micro-climate adaptable with human comfort and structural forms associated with the climatic positions which can also be applied to other cultures with the same climate. Furthermore, the economic status of each culture and its habitants used to suggest the size of the dwelling and its properties. In this context, the knowledge of the Sun rays, Magnetic poles and climate have been the three most influential factors in the creation of traditional dwellings.

Considering the high aspect, traditional architecture is basically in alignment with the traditional rule system or geomancy… Concerning the low aspect, the common characteristics of dwelling architecture are the presence of environmental context in which the buildings have been raised…

Further to the well-established rules and patterns, architects who supposed to follow the rules leading to human physical, psychological and spiritual well-being, had to be equipped with certain skills and characteristics as well. In India, a team of four experts symbolically derived from the mythological picture of Brahma who is the four-headed creator of the world, used to lead the construction process. Their roles and qualifications were as followed:

‘The Sthapãti (the master builder or the architects) directs the construction. He should be well versed in all the traditional sciences, healthy in mind and body and free from all vices. He should be trustful, joyous and friendly, possessing integrity of mind and body, and control over his senses. The Sūtragrahin (the surveyor) is the son or the disciple of the sthapãti and always carry our his orders with expertise. He should be skilful in measurement by the chord (sūtra) and rod (danda), as applied to buildings in their vertical and horizontal proportions. He should know the traditional sciences and should be an expert in drawing. The Takshaka (the carpenter and sculptor) cuts and carves, and is versed in working with wood, stone, iron, brass, copper, gold, silver and clay. He should be learned, kind, faithful and sincere towards his work and team. The Vardhaki, expert in painting, adds to the work accomplished by the takshaka. He should have the knowledge of traditional sciences and be capable of good judgement.’ Chakrabarti

From the above text, the emphasis on the character of the architects and the craftsmen beside their theoretical and practical knowledge of architecture is noticeable.

Further to possessing certain characteristics, ‘the architect should be equipped with knowledge of many branches of study (including medicine) and varied kinds of learning, for it is by his judgment that all work done by other arts is put to test,’ which is divided into theoretical and practical studies. The importance of the knowledge of medicine in this case denotes the significance of architecture in traditional societies as an influential factor on the health of its inhabitants.

Master builder in traditional societies was known as the person who has perceived the universal order, and is able to create dwellings in complete alignment with the natural laws and sacred symbols, to ascent the minds of the inhabitants in the way that they could perceive the transcendental realms as well, and therefore accelerate their evolution through architecture.

In fact in the middle-ages the architectural profession was gained after 3 to 7 years of apprenticeship under the supervision of a master craftsman who was supposed to transfer all the practical knowledge of craft including the knowledge of masonry, carpentry and other constructional methods, and a religious figure who was aware of the theoretical knowledge and the orders of the universe and its analogy to the human body as well as geometry and mathematics that would help the master builder to create places which transcendent the human soul. Only after being educated in both levels of physical and metaphysical knowledge the junior apprentice could become a journeyman who could work separately as a worker for gaining the practical experience; to gain the stage of being a senior master builder who was able to create places which nourishes both body and soul, the journey man had to present a master piece which shows his proficiency in the subject. In this era the building designer was commonly called the master builder and only by the end of this period the term “architect” became popular in architectural societies.

Available Traditional Rules and Patterns

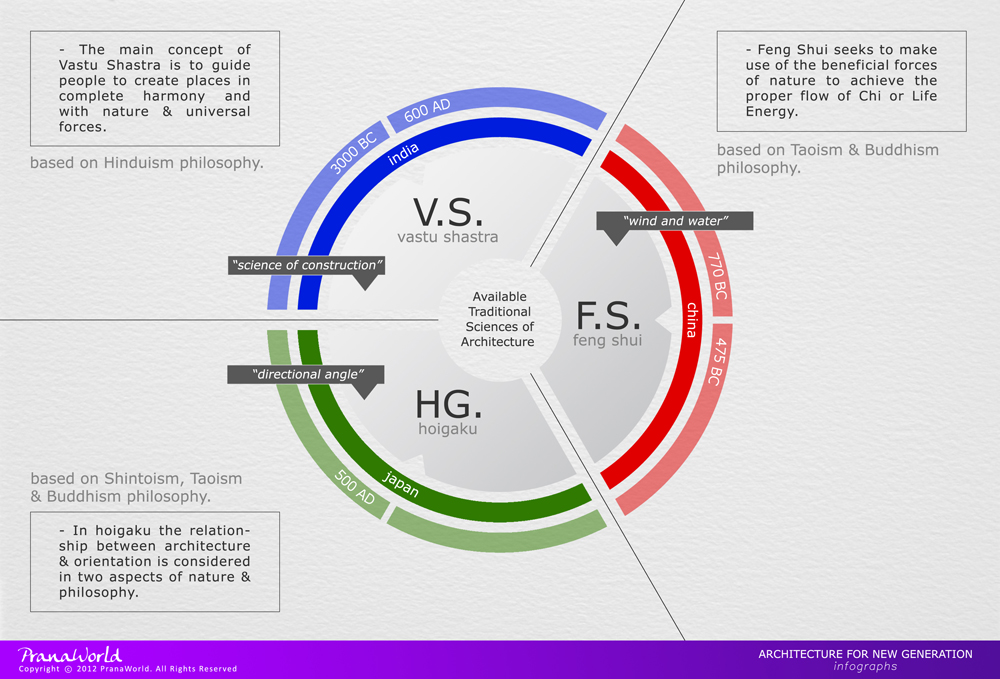

According to “Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World” there are only three remaining traditional architectural guidelines which are preserved from the ancient times and are partially being used today: Feng Shui, Vastu Shastra and Hoigaku which is a Japanese tradition.

According to “Encyclopaedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World” there are only three remaining traditional architectural guidelines which are preserved from the ancient times and are partially being used today: Feng Shui, Vastu Shastra and Hoigaku…

From the three preserved ancient systems of architecture, Feng Shui and Vastu Shastra are more important in scholars’ viewpoints as it is believed that Hoigaku is a latter form of Chinese Feng Shui and highly influenced by its principles and concepts. In fact Zen Buddhist philosophies originating in Japan has combined the Chinese principles of Feng Shui to create a unique aesthetic and order based on proportion, simplicity and harmony introduced as Hoigaku.

Hoigaku in Japanese term means “directional angle” in which the relationship between architecture and orientation is considered in two aspects of nature and philosophy. The nature consists of two elements of topography and climate which is associated with Japan’s climatic configurations and topographical elements while its philosophy is mainly derived from Shintoism, Chinese Taoism and Indian Buddhism. Therefore most of the laws of orientation have rooted in Chinese Feng Shui system which was imported to Japan around the 6th century and written down in 16th century as a complete guideline in architecture.

Feng Shui as the ancient Chinese principles of building is basically based on Taoist philosophies combined with Buddhism. Feng Shui, which is literally translated to “wind and water,” like Vastu Shastra, seeks to make use of the beneficial forces of nature to achieve the proper flow of “chi” or life energy. Some scholars believe that according to Chinese strong ancestor worship, Feng Shui was first used to suggest the ideal placement of grave sites so that people can gain the most benefit from the ancestors that later was developed into an advanced system of placement for homes and other buildings. Basically around 25 A.D. during the East Han Dynasty, the ancient literature and manuals of Feng Shui were found. As Feng Shui is primarily based on the theory of Yin-Yang, which was highly practiced during 770 to 475 B.C., it is believed that the rise of the Feng Shui teachings dates back to the same period. Since Feng Shui is applied for both Yin house, which is the house for the dead, and Yang house or the shelter for the living, it validates the idea of Feng Shui originated from the ancestor worship.

The main concept of Vastu Shastra, meaning “the science of construction,” on the other hand from the beginning, was to guide people to create places in complete harmony with nature and with the universal forces. The use of Vastu Shastra which is rooted in Hinduism philosophy dates back to the Vedic period appeared between 4000 and 2000 B.C. and the migration of Indo-Aryans to India. A section of Yajur Veda called “Sthapatha Vidya” which means the art of building, mainly deals with the principles of architecture and housing. In fact there are nearly 32 books written on the subject of Vastu from 3000 B.C. to 600 A.D. by various authors in Sanskrit language dealing with the construction methods, special placements of the house features and the rituals to be done in each stage. However before Ram Raz, the first scholar in this subject, very little attention was given to Vastu Shastra as the ancient science of architecture. The valuable studies done by Ram Raz on the Vastu Vidyas followed by Dr. P. K. Acharya opened a new horizon to discovering this traditional science until now.

As a matter of fact, Vastu Shastra later became the inspiration for the use of proportion and rhythm in architecture, derived from the Indo-Aryans’ elegant houses, temples and other architectural places. Nowadays Feng Shui and Vastu Shastra are applied widely not only by architects but also by ordinary people in their houses who want to lead a healthy peaceful life.

Get to know more about Feng-Shui & Vastu Shastra at the PranaWorld Store!

References

- Akkach, S. (2005). Cosmology and Architecture in Premodern Islam; An Architectural Reading of Mystical Ideas. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Akkach, S. (1997). In The Image of The Cosmos Order and Symbolism in Tradition Islamic Architecure. Islamic Quratey , 25-35.

- Alexander, C. (2004). The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe. Taylor & Francis.

- Barrett, J., Coolidge, J., & Steenburgen, M. (2003). Feng Shui Your Life. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.

- Bhattacharya, T. (1974). A Study on Vastuvidya or Canons of Indian Architecture. The United PRR Patna.

- Bovill, C. (1996). Fractal Geometry in Architecture and Design. Birkhauser.

- Chakrabarti, V. (1997). Vastu Vidya. In P. Oliver, Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World (pp. 552-553). Cambridge University Press.

- Cornelissen, H. (2005). Dwelling as a figure of thought. Uitgeverij Boom.

- Craven, J. (2003). The healthy home: beautiful interiors that enhance the environment and your well-being . Rockport Publishers,.

- Day, C. (2004). Places of the Soul: Architecture and Environmental Design as a Healing Art. Architectural Press.

- Gardner Gordon, J. (2006). Vibrational Healing Through the Chakras: With Light, Color, Sound, Crystals, and Aromatherapy. The Crossing Press.

- Gorgonia, M. D. (2008, 2 12). Pranic Feng Shui. (H. Fazeli, Interviewer)

- Hari, A. R. (2000). Amazing science of vaastu. A.R.Hari.

- Heidegger, M., & Hofstadter, A. (1975). Poetry, language, thought. Harper & Row.

- Kent, S. (1993). Domestic Architecture and the Use of Space: An Interdisciplinary Cross-Cultural Study. Cambridge University Press.

- Kumar, A. (2005). Vaastu: The Art And Science Of Living: The Art and Sciene of Living. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- M. Cox, K., & Eden Karn, A. (2000). Vastu Living: Creating a Home for the Soul. Marlowe.

- Marc, O. (1975). Psychology of the House. Thames & Hudson.

- Moffett, M., Fazio, M. W., & Wodehouse, L. (2003). A World History of Architecture. McGraw-Hill Professional.

- Oliver, P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World. Cambridge University Press.

- Powell, A. E. (2005). The Astral Body . The Theosophical Publishing House.

- Powell, A. E. (2003). The Causal Body. The Theosophical Publishing House.

- Powell, A. E. (2003). The Etheric Body.

- Powell, A. E. (2004). The Mental Body. The Theosophical Publishing House.

- Rapoport, A. (1969). House Form and Culture. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Rumi, J. a.-D., & Chittick, W. C. (1983). The Sufi Path of Love: the Spiritual Teachings of Rumi. SUNY Press.

- Salingaros, N. A. (1995). The Laws of Architecture From a Physicist’s Perspective. Physics Essays volume 8, number 4 , 638-643.

- Sang, L. (1996). The Principles of Feng Shui. American Feng Shui Institute.

- Shibata, T. (1997). Hoigaku: Japanese. In P. Oliver, Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World. Cambridge University Press.

- Silverman, S. (2007). Vastu: Transcendental Home Design in Harmony with Nature. Gibbs Smith.

- Snodgrass, A. (1985). The Symbolism of the Stupa. SEAP Publications.

- Sui, M. C. (2005). Achieving Oneness with the Higher Soul. Philippines: Institute for Inner Studies Publishing Foundation, Inc.

- Grand Master Choa Kok Sui . (2004). Miracles Through Pranic Healing: Practical Manual on Energy Healing. Institute for Inner Studies Publishing Foundation.

- Thayer, J., Brosschot, J., & Gerin, W. (2006). The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A Review of Worry, Prolonged Stress-Related Physiological Activation, and Health. Scopus, Volume 60, Issue 2 , 113-124.

- Tuan, Y. F. (2001). Space and Place: the Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Vitruvius, & Morgan, M. H. (1960). Vitruvius, The Ten Books on Architecture. Dover Publications, Inc.

0 Comments